Britain’s electricity grid is creaking. This is not good news

This is a post about arguably the most important & underdiscussed issue as we push towards net zero. The UK electric grid is creaking - big time. It could trigger blackouts & even get in the way of those climate ambitions. This is a very big deal. But let’s begin our story with something else. A bit of history. The first power station...

It’s sometimes forgotten that the world’s first conventional power station (eg with steam turbines powered by fuel) was not in New York or Berlin but in London. Holborn Viaduct Power Station opened in early 1882. It lit up thousands of lights around the city.

The introduction of electricity was one of the most important - some would argue the single most important - technological leaps in history. Electricity didn’t just make light brighter and cleaner than gas or kerosene lamps. It lifted productivity everywhere.

The introduction of electricity represented a second Industrial Revolution. Factories could replace inefficient steam driven machines, like the one below, with electric motors.

It had an instant and dramatic impact on productivity. Indeed, there are many economic papers on this. You can read a good one here. See these charts that tell some of that story:

So whichever country introduced electricity first could be first to reap economic benefits. Hence it’s not insignificant that London had the first conventional power station. But here’s the thing: actually Holborn viaduct station isn’t a story of triumph. It’s a cautionary tale…

Because the power station was shut down a few years after opening. No sign of it is left today. Most people have forgotten it. When they think abt the world’s first serious power station they think of Thomas Edison’s Pearl Street power station in New York.

While other major cities embraced electricity, London fell behind. As of 1913 electricity consumption per capita was as follows:

Chicago: 310kwh

Berlin: 170kwh

London: 110kwh

This btw is all from Thomas Parke Hughes’ Networks of Power - an amazing book everyone needs to read. Anyway, the intriguing thing is that the Holborn power station had precisely the same technology as the Pearl St station. Both were Thomas Edison designs, generators etc. Why did London fail while NY succeeded? In short: regulatory resistance.

Making electric power a success wasn’t just abt building a power station or buying new machines. You also needed to construct a whole GRID of wires and (when everyone went AC) transformers and other kit. It was expensive & disruptive… Look at Edison’s estimates for wire costs…

Local and national UK politicians were happy with gas lighting. They saw no reason why they should have to tear up the streets of their city to install the necessary pipes for a broader electricity system. Interestingly among the most resistant was the iconic Joseph Chamberlain.

Anyway, the rest is history. The UK entered the electric age late, but eventually caught up. Roll on to the postwar period & it built a national grid of pylons and transformers in the 1960s which was so ahead of its time it provided more power capacity than we’d need for decades.

All of which brings us more or less to today. We don’t spend much time thinking about grids these days and to some extent that’s a story of success. UK system holds up pretty well most of the time. Power cuts are relatively rare. But behind the scenes the system is creaking.

You can break this story down into two parts. There’s the issues with the main transmission lines which get the power from generators towards different regions. This bit is managed by National Grid. Consider it the electricity “motorway system”. Lots of pylons etc.

Here the issue is that this “motorway” system was built for a finite set of mostly coal-fired power stations dotted around the country, close-ish to where the power was needed. Roll on to the 2020s and we have shut down most of the coal and are relying increasingly on wind power.

This is obviously great for the environment. There was a dark side to that first power station: it was also the beginning of the coal power era, where we pumped enormous quantities of CO2 and sulphur into the sky. Ending that era is a critical element in combating climate change.

And this is mostly a good news story! In recent years we have been building and deploying wind turbines faster than anyone had expected with the upshot that the global power breakdown is changing, fast. Chart from @energy_said, a must-follow on all things energy.

However, switching from a grid with a relatively small no of dispatchable coal power stations to one with 100s of wind turbines in the N Sea & Scotland is a BIG shift. Current grid isn’t set up for it. For one thing we need lots more pylons (the motorways) to move the power…

But those in Norfolk and other areas where the pylons are needed to bring the power over from the wind farms are NOT happy. They are already contesting the plans and given the nature of Britain’s planning system you’d have to say they’ve got a good chance. The upshot of this is that a LOT is being asked of the national system. The physics of this are complex (I know very little about how this works - others like @guynewey know far more) but essentially @NationalGridESO is having to step in to keep things chugging away a LOT these days.

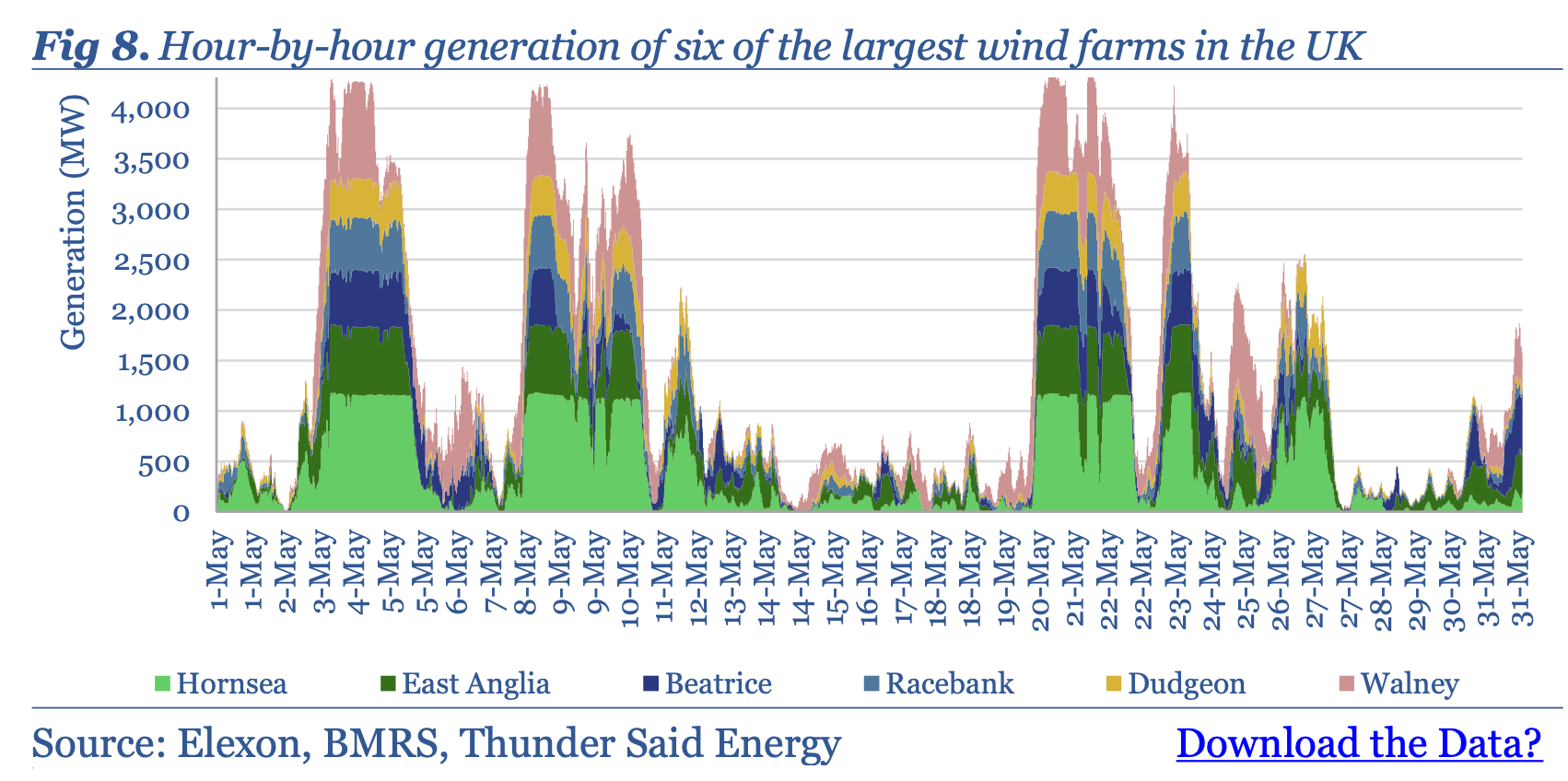

(Another issue we’re nowhere near resolving is what to do about the intermittency of renewables. Sometimes wind blows a lot, sometimes not at all. Good chart on that below, again from Thunder Said Energy. For all that wind turbines are getting cheaper, that doesn’t account for the need to back them up. But this is a whole other topic which demands a whole other article. One day...)

Anyway, this shortage of grid capacity is already threatening UK plans to eliminate carbon emissions for electricity generation by 2035. One firm planning a new wind farm was recently told the earliest it could be hooked up to the grid was 2034(!) This is… problematic.

But arguably the biggest issue is the other bit of the grid - not the “motorways” but the “A and B roads”. The delivery of electricity to households and businesses. Controlled by 6 Distribution Network Operators (DNOs), regional monopolies who own the wires/transformers near you.

We don’t directly pay these regional monopolies but since they own the cables and transformers, they take a cut on our bills. And they’ve done extraordinarily well in recent years. A recent report from Common Wealth says they’re the most profitable sector in the country. Chart from it here:

Now that would be fine if they were doing a swell job of improving networks but evidence to support this is scant. If we’re all going to have electric cars and maybe heat pumps too, then we’ll need more cabling and power capacity everywhere. But many of the DNOs aren’t delivering…

Consider this FT story from earlier this year: several London authorities, where new housing is desperately needed, are being told they will have to wait years, maybe more than a decade, for new developments because of a lack of local grid capacity.

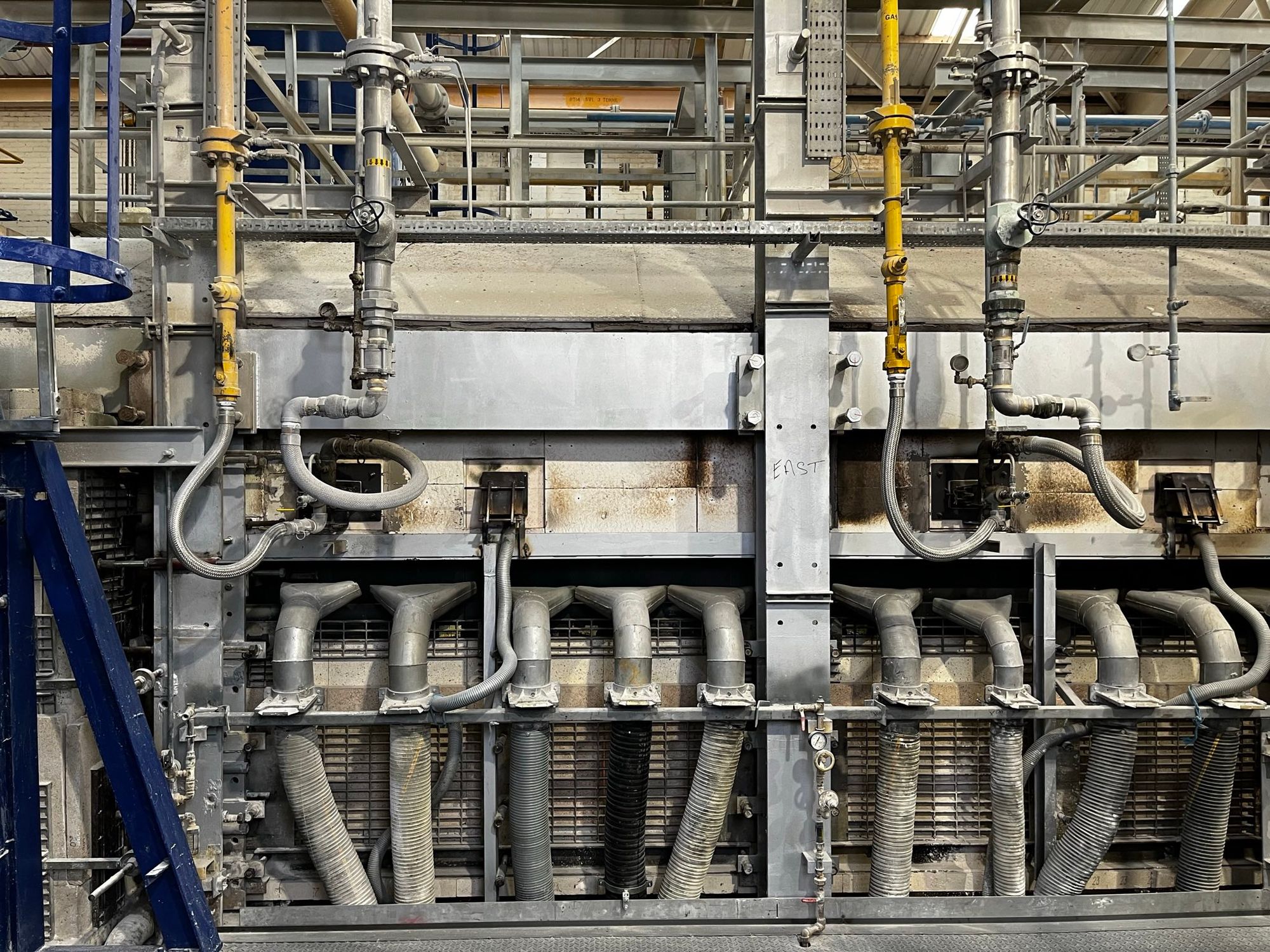

Or here’s another example: a fibreglass manufacturer near Wigan, Electric Glass Fiber, a UK subsidiary of Japanese group Nippon Electric Glass. Fibreglass is amazing stuff: the backbone of the energy transition. It’s what we use to make wind turbine sails & lightweight car parts which are essential for electric cars.

But right now turning sand into fibreglass involves heating it to very high temperatures in a gas furnace. Up until recently everyone thought this might be the only way to do it (and hydrogen furnaces have their own problems and inefficiencies). However, the plant at Wigan reckons it can replace its carbon-emitting gas furnaces with state-of-the-art electric furnaces. This would be quite exciting!

The UK, whose govt always goes on about wanting to be “world leading” in the energy transition could genuinely lead the world here with the first at-scale carbon neutral fibreglass site. That ought to be quite an enticing prospect, so the MD at Wigan looked into getting the extra power he’d need for that new electric furnace. But when he went to the local DNO, Electricity Northwest he was told that the only way he could get that power was to pay £30m for new cabling and transformers. Given the entire furnace was supposed to cost £70m, this was prohibitive. So the Japanese parent company began to look elsewhere.

Talk to enough people in industry and construction and you hear loads of these stories. They’re not the only problem with building our way to net zero. The obstructiveness of the planning system looms large too. But grid capacity is increasingly a major issue.

Now, just this week UK energy regulator Ofgem announced plans to tweak the regulation of DMOs which it says will allow them to invest more in local grids. Sounds encouraging, right? And perhaps it will mean that electric furnace at Wigan will be possible without that extraordinary extra cost. But there are still big question marks, among them: how, given the stupendous scale of investment needed, is Ofgem convinced that consumers won't have to pay an extra penny? Not altogether clear, so the proof will be in the pudding.

But there’s a deeper issue here which is that it’s hard to see how you can unblock some of these issues without central govt intervening, or at the v least, being clear about its vision for energy. More heat pumps? More hydrogen? More insulation? Smart grids? Very unclear at moment. This government seems even more averse to producing a concrete “industrial strategy” (I mean as opposed to a pretty white paper with no money behind it) than any of its predecessors. Yet it’s hard to see how you get to net zero without one.

Why? Because getting to net zero will involve an enormous set of industrial shifts, which amounts to re-doing the Industrial Revolution all over again. A big, hard job. But also a MASSIVE opportunity for whoever does it well/first. And on the other side of the Atlantic, Joe Biden is pouring hundreds billions of dollars into power networks, renewables, batteries and the rest via his (oxymoronically-named) Inflation Reduction Act. So investors in green energy are increasingly abandoning the UK for the US.

It leaves one pondering a question, which I explore in a Times column today. Back in the 1880s the UK ditched electricity because it didn’t want to dig up all its streets for new wires. It chose entrenched industries (gas) over the future. It allowed building restrictions to temper its ability to absorb a new technology, and this mistake set back the economy for decades.

Are we in danger of doing precisely the same thing all over again…?

Comments ()