Energy and Inflation: A Series of Unfortunate Events

Sellindge is a village in Kent just off the A20 between Ashford and Folkestone. It is so small - just over 1,000 inhabitants - that most people barely notice it as they speed down towards the English Channel in their cars or on the Eurostar.

But if you were passing by last night or this morning you could hardly have missed Sellindge, for visible from miles around is a plume of black smoke pouring into the sky from a facility just outside the village. That facility, owned by National Grid, which operates Britain’s electricity network, is where one of the main cables which brings electricity into this country plugs into the UK grid.

Quite what happened to cause the fire is somewhat unclear but what is becoming clear is that it is serious: serious enough that the cable will be out for at least a month.

There has been an immediate impact: the UK is down one gigawatt of power and, as you can see from the chart above, the total imports from France have dropped to the lowest level in more than six months.

Now, it’s tempting to say: so what? The UK’s total electricity use is somewhere in the mid 30s gigawatts, so this doesn’t exactly make a massive difference. Nor is this the only cable coming to the UK from France - there is another, which is running fine at the moment.

There are interconnectors coming from Belgium, the Netherlands and Norway too, upon which the UK has relied to top up (or occasionally export) its electricity for some years. So the UK is hardly disconnected from continental electricity. Indeed, National Grid expect to be able to accommodate all its power needs tonight and in the coming months. There is no prospect of power cuts, they say.

But here’s why what’s happened in Sellindge matters: because it is only the latest in a whole series of episodes which are both pushing up electricity prices and are begging bigger questions about our energy future. In other words, this really matters for all of us and it is irretrievably bound up in our efforts to eliminate carbon emissions and to get to net zero.

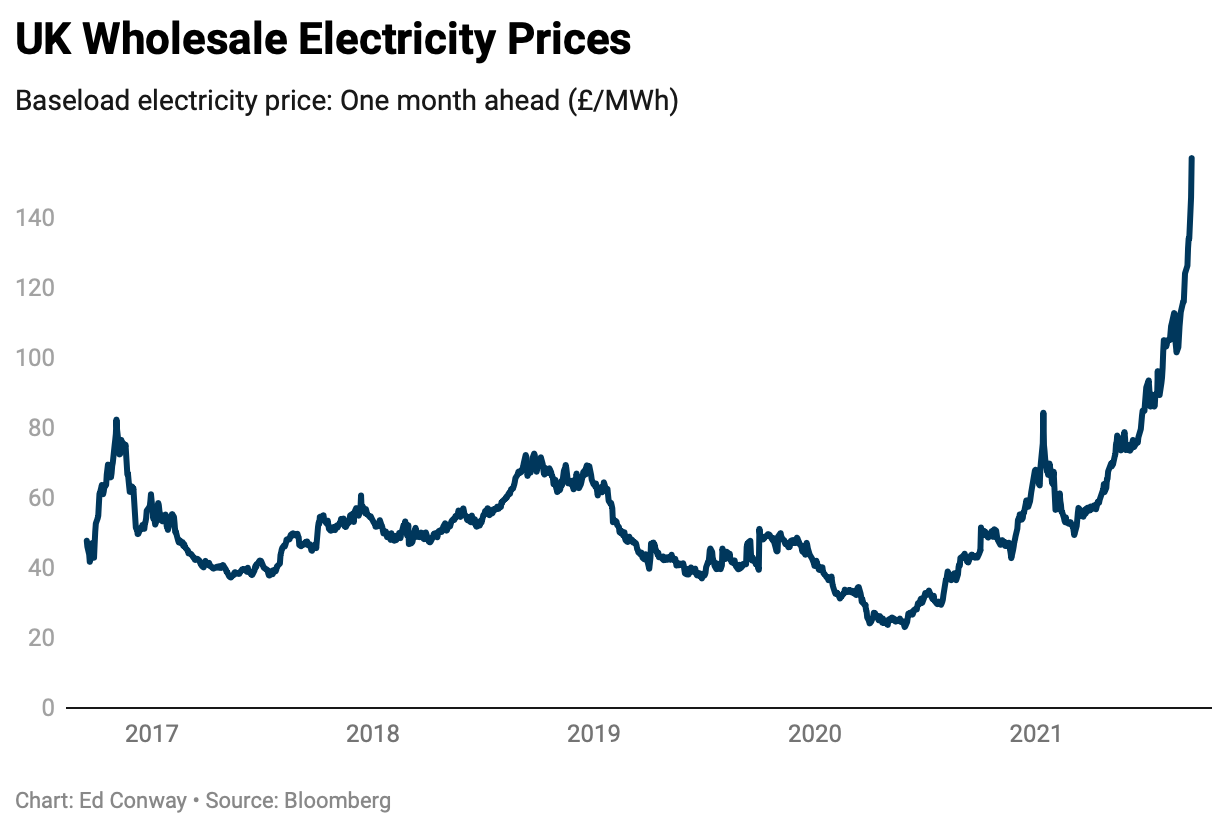

Even before that fire broke out, in fact, UK electricity prices were at unprecedented levels. Consider the chart below:

This nearly vertical line is the wholesale price of electricity in the UK and, as you can probably see, it’s going through the roof. In fact, this chart somewhat underplays the drama, for if you look not at the price of electricity one month ahead but one day ahead, you see an even sharper increase, up by about 300% in the past two or three weeks. Sharper still, post-Sellindge.

When you consider that a) these are the prices which will eventually be passed onto consumers b) they are way, way higher than they have ever been and c) the cold weather hasn’t even begun, well, you are starting to get the picture. This is big stuff. This chart may turn out to be the story of the coming months - especially since millions of households are about to see a sharp cut in their universal credit (a big chunk of which is invariably spent on energy bills).

Sellindge is only a tiny part of this tale. Far more consequential are a few other things: first off, gas prices are very high at the moment - and given gas is used both for heating and for electricity generation, that really matters. I could just as well have used a chart of gas prices above, since the shape is much the same as that one. And those prices are high not just in the UK but across most of Europe.

Why? Again, there is no single explanation. One is that Russia seems to be rationing Europe’s supply of gas, for reasons lots of people have theories about but no-one can quite pin down for sure. There have been shutdowns of gas platforms in the English and Norwegian North Sea - repairs and routine maintenance that was delayed because of Covid. In a “normal” year this wouldn’t be a problem were there a ready and large supply of liquified natural gas - the kind of gas you can put in ships - but many of those ships are in Asia, where hot weather and air conditioner has increased demand for power. Some are in the US, which is holding on to some gas ahead of the hurricane season and winter (especially given the electricity problems in Texas last winter).

Again, this might all be manageable if Europe had decent stockpiles of natural gas waiting to be used, but it doesn’t. As you can see from this chart, stockpiles are at the lowest level for a September in many years. Even these stockpiles might just about suffice if this was a quiet period for the economy, but it’s not: following shutdowns across much of the world, economic demand and spending is rising very fast indeed, which in turn is creating more economic activity, which in turn has pushed up electricity (and hence gas) use.

All of that explains why energy prices have risen in recent months. But it doesn’t end there. In a “normal” year countries like the UK, which have lots of wind turbines, could expect to generate a decent amount of electricity from the wind. But the wind simply hasn’t been blowing as much as it usually does at this time of year. To put this into perspective, this time last year the UK’s wind turbines were generating more than 5 gigawatts on average. As of this morning they were generating less than 3 gigawatts.

Put it all together and you can start to see why the UK, in particular, is so exposed. This country’s energy strategy has long been to increase our output from alternative energy (especially wind power, since the North Sea, it turns out, is perfect for wind generation) but to turn to backup power stations on the days when there’s no enough wind. In recent years many of the coal-fired power stations have been shut down, an understandable consequence of the carbon trading schemes which make this especially pollutive form of electricity all the more expensive. The good news is that as a result the UK has cut its carbon emissions significantly. But in doing so, it has become yet more reliant on natural gas for times like this. And gas (see above) is expensive.

You see where we’re heading? It seems pretty certain that electricity and gas prices will rise yet further in the coming months - and make no mistake, UK consumers tend to notice when that happens. And when voters notice it, politicians notice it too.

All of which brings us to November, when the COP26 summit of world leaders will take place in Glasgow. These meetings often tend to be somewhat abstract: leaders are making decisons which will are designed not to bite for years. There are big promises on cutting emisssions, but they often real a little unreal. Not this time.

This time, this crucial meeting will happen against a backgrop of UK consumers (and, most likely, much of Europe too) facing a real squeeze because of high energy prices. And while climate change policy, and wind turbines, are not the only contributory factor, they are at least a part of it. In other words, that fire at Sellindge, alongside what's happening to gas supply on the other side of the Channel, may mark a watershed: the end of climate change policy as an abstract and the beginning of very real, and sometimes unpalatable consequences. The arguments will get tougher and chewier and politicians' mettle will be tested.

None of this, I should underline, is a surprise in the slightest. This would always happen at some point. At some point the cost of rebuilding our energy systems would become a noticeable part of consumers bills (some would argue it already is; after all, European energy prices are considerably higher than most other parts of the world for precisely this reason. But you see my point). But perhaps due to this series of events, that watershed is coming a year or two earlier than expected.

The fact that energy prices are rising so fast at the moment is not just because of climate change policies, but it is a pretty good illustration of the kind of dynamic that could play out time and again in the coming years. It does not charge the arguments for or against going ahead with these policies - but it certainly raises the stakes on both sides. It underlines that just as important as renewable energy is investing in some form of alternative energy generation or, for that matter, energy storage, to help fill in those gaps. That could be more batteries, it could more pump storage facilities, it could be gas power stations with carbon capture or indeed some other system we’ve yet to develop.

But this will be expensive. Very expensive - enough to push energy prices up even further. And time is running out, because for many of these solutions it's not just a question of buying them off the shelves and implementing them. Many of them have never been tested at scale.

That this is all happening at one and the same time as a big spike in inflation is not exactly a coincidence, though again the inflation story is not really one story but lots of them: poor harvests of some foods and timber, shortages of crucial metals, problems in the semiconductor supply chain and a lot of post-Covid demand. It is all pushing up prices. There are plenty of major commodity price indices which look almost exactly like that energy chart above. Case in point:

The inflation debate right now feels somewhat similar to that energy-specific debate. This might not feel like a traditional inflationary spiral: there are lots of discreet reasons why prices are rising. But in a sense that hardly matters. What matters is whether employers and employees look around at rising prices and start pushing up wages, which in turn pushes prices even higher. Inflationary spirals almost always begin with an unfortunate sequence of events. They end, more often than not, in economic misery.

Comments ()